Coal seam gas exclusion zones fail community expectations

After considerable public pressure, the Government has finally implemented coal seam gas exclusion zones around certain areas in NSW. These have been implemented via amendments to the State Environmental Planning Policy (Mining, Petroleum Production and Extractive Industries) 2007 [Mining SEPP].

Implementation of these exclusion zones is an admission that coal seam gas is unsafe, and this ban must be extended to include agricultural land, water catchments and sensitive environments.

With this announcement, there is an opportunity to make public submissions on the Stage 2 coal seam gas exclusion zones, critical infrastructure mapping, and strategic agricultural land mapping, which are on public exhibition until 8 November. Make submissions here.

While it’s important to comment on the accuracy of these maps, it’s also important to contact the Government and other members of Parliament to let them know the exclusions don’t go far enough. They don’t protect all residents, they don’t protect water catchments or agricultural land, and they don’t protect our precious environmental areas, such as the Pilliga forest.

Below is information that helps make sense of the latest changes, along with key concerns the Government needs to address to ensure that coal seam gas does not industrialise NSW.

What the SEPP does

- Introduces coal seam gas exclusion zones on and around residential areas, and on critical industry clusters, and prohibits coal seam gas development in such areas.

- Maps strategic agricultural land, future growth areas and appoints gateway panel to assess coal and gas projects on BSAL land.

- Only applies to coal seam gas, not other unconventional gas such as tight sands or shale gas.

- Applies to new exploration and production activities - not where environmental assessment for development approval has already been notified by the Director General before 10 September 2012.[1]

Residential zones

- Applies coal seam gas ‘exclusion zones’ to residential land zoned R1, R2, R3, R4 and RU5 (villages).

- The residential exclusion zones cover 2.344 million hectares across all 152 local government areas of the state.

- Pipelines are allowed within the 2km ‘buffer zones’,[2] which means there may be pipelines up to the boundaries of residential areas.

- No publication of residential ‘exclusion zones’ maps – only future growth areas - therefore leaving communities with uncertainty as to whether their land is protected. Leaves individual land owners to check their land zonings with council LEP. Residents may perceive they are protected when in fact they’re not.

- Excludes rural dwellings from protection, which means these people will be the collateral damage of coal seam gas expansion. This will unfairly impact those living in rural communities and large lot residential areas. Large lot residential areas zoned R5 will not automatically be afforded the protection that other residential areas are given, unless they fit the village criteria. Therefore large lots residential estates such as Waterview Heights in South Grafton,[3] Forbesdale and Thunderbolts residential estates in Gloucester,[4] and the residential areas around Crookwell, Gunning and Taralga in the Upper Lachlan LGA[5] will not be protected by the exclusion zones.

- Government is proposing to extend the exclusion zones to seven ‘‘rural-residential’’ villages including parts of Goonengerry, Jerrys Plains, Broke and Bulga; all of Modanville, Camberwell and Sutton Forrest; and to land earmarked for future housing in 56 council areas.[6]

- Councils can still opt out of exclusion zones,[7] and although no councils have said they’d opt out,[8] this option will remain into the future, and will lead to risks of undue influence and corruption.

Biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land & Gateway Panel [applies to coal and gas]

- BSAL guidelines only protect agricultural land that is the ‘best of the best’.

- Although 2.8m ha of BSAL has been mapped (1m ha more than previously), this is only 3.5% of state.

- The Director-General of planning will be the one that determines verification certificates for BSAL, not an authority with any experience of agriculture or any independence from the assessment process.

- Areas mapped BSAL do not provide protection per se, merely means they go through the gateway process which has no power to reject a project.[9]

- 90 days for Gateway panel to make assessment[10]

- Section 17H of the Mining SEPP say the Gateway Panel “must determine an application by issuing a gateway certificate in accordance with this Division.” However, if the Gateway Panel runs out of time for their assessment, a certificate with no conditions attached will be automatically issued.

- Section 17J (3) (a) says that in the event that a proponent fails to provide further information requested by the Panel, they can “reject and not determine the application” but this is not consistent with section 17H.

- Gateway panel won’t assess projects that were issued with formal assessment requirements before September 2012 (when Gateway was announced)[11] – therefore only three existing mine proposals would need to go through the new gateway panel - Spur Hill mine near Denman, the Bylong Coal Project and the Caroona Coal proposal for the Liverpool Plains.[12] Department of Planning spokesman said a number of projects, such as the Drayton South coalmine proposed near the Darley and Coolmore horse studs, would also be referred to the panel for “advice”.[13]

- Gateway panel members[14] have already been criticised for having links to the mining industry.

- Mining on BSAL must also be referred to the Minister for Primary Industries for advice on the project’s impacts under the government’s aquifer interference policy,[15] and to the Commonwealth independent expert scientific committee for advice about water impacts.[16]

- Exempt from both the exclusion zones and the gateway assessment process are any horse studs or vineyards that gas or mining companies have owned before its draft land-use policy was announced in September 2012. This is a major loophole and will lead to a ‘Swiss-cheese’ effect considering mining companies have been buying up land in the Gloucester and Hunter valleys for years.[17]

Critical Industry Clusters

- Critical industry clusters only protect horse studs and wineries – not other enterprises such as horticulture, cropping, grazing, dairy, poultry etc

- No ‘ 2 km buffer zones for CIC’,[18] which means industry can drill up to the boundary.

- Reduction by 11% of the amount of land that comprises an Upper Hunter ‘‘critical industry cluster’’ of horse studs and vineyards compared to September draft land-use plan[19]

- Mapping of vineyards has been a complete shambles.[20]

- In allegations of collusion regarding mapping of CICs, the Department of Primary Industries says “it appears that the two vineyards in Broke owned by AGL were inadvertently omitted from the maps”.[21]

Other key concerns

- 2 km buffer zone is unscientific and arbitrary – 2 km buffer zones are inadequate when considering that air, light, noise and water pollution can travel many kilometres.

- Protections only apply to coal seam gas, not other forms of unconventional gas such as tight sands and shale gas, which is increasingly being targeted for exploitation. Northern NSW has tight sand gas deposits, which may well mean the 2 km protections do not apply.

- Water catchments[22] and other sensitive environments still not protected

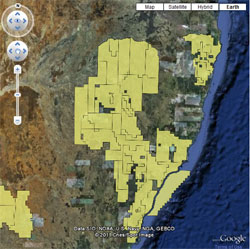

- Insufficient area of land protected - NSW land area is 800,000km2, which is 80 million hectares. Government is saying they’re protecting 5 million hectares of residential and farmland, which is only 6% of the state (3.5% of this 6% is BSAL, which is still open to mining). CSG licences cover approx. 25% of the State. Brad Hazzard says the policy “still allows industry to access 90% of the land area that has the resource”.[23]

- Protection excluded where project already approved - the buffer zones will not apply to exploration or production licences that have already been approved.[24] This means that the buffer zones will not protect Gloucester residences from the Stage 1 project approval (pre March 2011)[25] but would apply to Stages 2 & 3. This would mean Metgasco’s drilling near Casino township (pursuant to Richmond Valley Power Station project approval) may be allowed.

- Strategic regional land use mapping still incomplete - SRLUP maps have only been completed for 2 areas in the state – Upper Hunter and New England North West, therefore leaving most of the state unmapped.

- Gateway and Mining SEPP do not promote existing rights – such as those that exist in sections 71 & 72 of the Petroleum (Onshore) Act relating to restrictions on exploration and production. Landholders may incorrectly assume that if they do not satisfy the criteria for BSAL, then they have no choice but to allow access. As it stands, landholders have the right to deny access (albeit contested) for exploration under soil conservation works etc and for production on cultivated land.

Stakeholders

- NSW Irrigators “happy to coexist with industry”, but want 2 of the following 3 demands met:[26]

- detailed baseline data

- making the aquifer interference policy a binding regulation giving control of water to the Water Minister

- extending critical industry cluster protection to all irrigation farms

- NSW Farmers

- “The exclusion zones apply to towns and population centres, they don’t apply to agricultural land or water. The agricultural land and water is mapped as biophysical Strategic Agricultural Land and that land is not ruled out of development.”[27]

- “[Gateway] panel lacked teeth.”[28]

- “this government has chosen to ignore all feedback and deliver effectively the same Gateway Process that was offered up initially for public comment”[29]

- Wants the aquifer interference policy to have teeth[30]

- There is no gate in the gateway[31]

- APPEA – “A policy anchored in blanket no-go zones to “protect” areas from an industry that has been producing natural gas safely in Australia for decades is not a policy based on sound science or experience,”[32]

- Lock the Gate[33]

- Lock the Tweed

- “Lines on a map will not stop air and water borne contaminants from impacting on communities”

- Cane land or eco-tourism not included as CIC

- Lismore City Council – wants 2km buffer zone extended to schools (particularly country schools)[34]

- Tweed Sugar Cane Growers Association - “Intensive cultivation is just not compatible whatsoever with CSG and we will do whatever it takes to protect our farming land.”[35]

Impact on Projects

SEPP seems to confirm that AGL’s expansion of its Camden project south of Sydney cannot proceed, nor its Hunter project. Expansion of the Gloucester project beyond the already approved first phase may also be impossible.[36]

Santos – Mr Baulderstone said Santos would not be affected by the NSW legislation and was happy the state government had agreed to support its Pilliga project and AGL’s Gloucester project.[37]

The Australian article suggests “most of NSW’s 13 CSG operators will be largely unaffected.”[38] [5 October]

Summary of Key Concerns

- Fails to protect water catchments or sensitive environments (such as the Pilliga).

- Fails to protect agricultural land (BSAL land will still be mined/drilled via Gateway process).

- Fails to protect rural residents.

- Allows councils to opt out from protection, leading to risks of undue influence and corruption.

- Allows pipelines within the 2 km buffer zone.

- Does not protect against other unconventional gas exploration, such as tight sands and shale gas.

- Only protects narrowly defined critical industry clusters – horse studs and wineries.

- Gives no protection to Gloucester residents where 110 wells have already been approved and where large lot residential estates have not been given residential protection.

- Diminishes landholders’ perception of their existing rights under the Petroleum (Onshore) Act & Mining Act relating to access agreements and restrictions on exploration and production (albeit limited).

Documents & links

SEPP overview by law firm Clayton Utz

Strategic Regional Land Use Policy website

Gateway assessment panel & members

[2] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_epi/seppppaeia201320135811004.pdf, clause 9A(4)

http://www.planning.nsw.gov.au/Portals/0/StrategicPlanning/FAQ_Stage_one_CSGExclusion_zones.pdf

http://www.theherald.com.au/story/1817021/exclusion-zones-come-into-force/

[3] https://majorprojects.affinitylive.com/public/04d939b1caf535e1b4a4a8e489b42040/Government.pdf, p 9

[4] https://majorprojects.affinitylive.com/public/04d939b1caf535e1b4a4a8e489b42040/Government.pdf, pp 86-90

[5] https://majorprojects.affinitylive.com/public/04d939b1caf535e1b4a4a8e489b42040/Government.pdf, p 146

[7] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_epi/seppppaeia201320135811004.pdf, clause 9A(3)

http://www.northerndailyleader.com.au/story/1385071/councils-may-exempt-coal-seam-gas-bans/

[8] http://www.2gb.com/audioplayer/16766#.UkyqIYanoTl

http://www.brisbanetimes.com.au/nsw/ban-on-fracking-to-protect-more-homes-20131002-2usuf.html

[11] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_epi/seppppaeia201320135811004.pdf, clause 21(1)

http://www.theherald.com.au/story/1821533/three-mine-plans-to-face-environment-panel/?cs=305

[13] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_epi/seppppaeia201320135811004.pdf, clause 21(2)

http://www.theherald.com.au/story/1821533/three-mine-plans-to-face-environment-panel/?cs=305

[14] http://www.mpgp.nsw.gov.au/?action=page&page=members

[16] http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/legis/nsw/num_epi/seppppaeia201320135811004.pdf, clause 17G(1)(a)

http://www.theherald.com.au/story/1821533/three-mine-plans-to-face-environment-panel/?cs=305

[17] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-10-15/gas-company-vineyards-missing-from-critical-industry-maps/5022490

[18] See Note at [3] in Schedule 1: https://majorprojects.affinitylive.com/public/60edd5b262ca1f301fc59d4725c4285f/State%20Environmental%20Planning%20Policy%20(Mining,%20Petroleum%20Production%20and%20Extractive%20Industries)%20Amendment%20(Coal%20Seam%20Gas)%202013.pdf [e2013-259-42.d07 24 September 2013]

[20] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-10-16/wine-mapping-process-an-incompetent-shambles3a-greens/5025190

[21] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-10-16/wine-mapping-process-an-incompetent-shambles3a-greens/5025190

[23] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-10-04/farmers-and-environmentalists-voice-concerns-over/5000500

http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-10-04/nsw-planning-minister-responds-to-csg-critics/5000496

[25] http://www.gloucesteradvocate.com.au/story/1820569/procedural-fairness-the-reason-for-no-gas-exclusion-zones/

[26] http://www.therural.com.au/story/1817922/irrigators-seek-balance-on-coal-seam-gas-issues/?cs=1532

[27] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2013-10-03/nsw-says-95-per-cent-of-dwellings-excluded-from-csg-mining/4995100?§ion=news

[28] http://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/csg-limits-to-cost-jobs-lift-gas-prices/story-e6frg6n6-1226732606316#sthash.ZDzVpqpg.dpuf

[31] http://www.theland.com.au/news/agriculture/general/news/gaps-left-in-gateway/2674380.aspx

[34] http://www.northernstar.com.au/news/no-csg-near-schools/2046455/?utm_campaign=News+PM&utm_source=Northern+Star&utm_medium=email#.UlZBcR4PuOc.facebook

[36] http://www.farmweekly.com.au/news/agriculture/general/news/drilling-ban-sparks-energy-shortage-fears/2673718.aspx